Chapter1

The guardians of Lake Ashi—Supporting the lake's ecosystem through circulation

The boat speeds along, breaking through the mist that rises from the lake surface. Beyond the white haze, a forest spreads out. A mass of mountain cherry blossoms adds colour to the otherwise monochrome landscape.

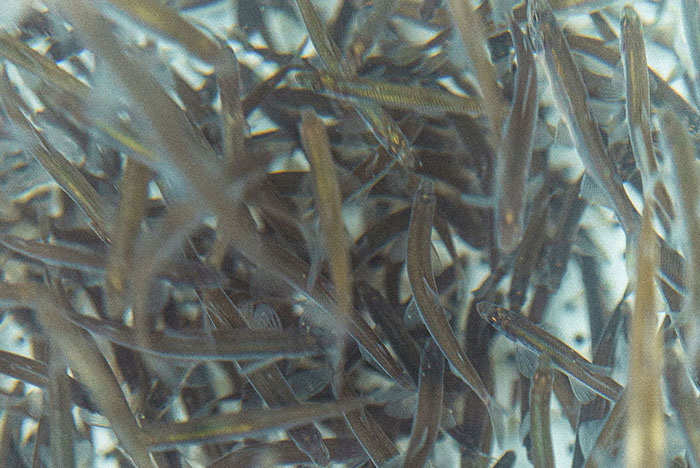

As the view widens, two boats handling fishing nets close to the lakeshore appear in sight. A school of fish gathered in the shallow water, roughly 10cm deep, were swimming toward the boats.

Hurrying across the fog-covered lake to the fishing grounds.

Motoyoshi Oba and Tomonari Oba collect Wakasagi caught in a net at Shirahama Point.

Wakasagi gather to spawn in the shallow water. By setting nets there, the fish follow the nets and enter the gathering nets near the boats.

Wakasagi in the fish nets is quickly removed and placed in air-fed polyethene containers.

They swam and entered the gathering-net set at the end, just as if the nets between the boats were guiding them. Then, they are scooped into a great polyethene container with a large landing net. Countless dazzling silver flashes in the blue container—these are the beautiful Hypomesus Nipponese (Wakasagi, Japanese Smelt) in its spawning season.

“Knowing where to position the nets accurately is difficult. A mere 10 meters could make a difference resulting in no catch,” says Tatsuya Fukui, head of the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative Association. He relaxes and smiles at the sight of the catch. The Wakasagi collected is now divided into four containers, each weighing 5 kg and amounting to 20 kg in total. The nets are placed at several points, and the average daily catch is 50-70 kg, with this year’s record being 144 kg.

The catch is transported immediately to the hatchery by cooperative members standing on the barges.

After weighing, the fish are released into the tanks.

As soon as the fish are transferred, the two boats speedily move to the next point while Mr Fukui returns to the fish hatchery on the opposite shore. The mountain lake on a wet April day is still terribly cold. However, Mr Fukui heads along while humming a tune. For him, this is no comparison to a February day when the splashes that cover the body will instantly freeze.

Back on the barge at the hatchery, Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative members are waiting. They lift the polyethene containers full of water and carry them away in pairs, working in a coordinated and seemingly effortless manner. The fish is weighed and released into the tank when finally, Mr Fukui takes a deep breath. “If the fish becomes weak, it’s harder to trigger the spawning process. That’s why it’s really a game of speed.”

Sweat runs down his smiling face, and a sense of fulfilment is present.

Lake Ashi is located at an altitude of 723 m in Hakone, Kanagawa Prefecture. It is a caldera lake created by volcanic activities, and the water is sealed by the surrounding mountains. Due to its unique environment, few rivers flow into it, and it was originally inhabited by only a few species of fish other than sea trout. Aquaculture began in Lake Ashi in 1880 with the hatching and release of Honmasu-trout and salmon.

“Lake Ashi was chosen because of its proximity to the metropolitan area and good water quality. The purpose of aquaculture at the time was to increase fish stocks against food shortages.”

In 1918, Wakasagi were transplanted from Kasumigaura in Ibaraki Prefecture amid repeated trials of releasing salmon and trout, both of which the Japanese people favour.

In 1949, when then Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida erected the Heiwa Torii gate at Hakone Shrine, Wakasagi from Lake Ashi were presented to the Imperial House of Japan.

Since then, the tradition has continued, and the first fish caught at the start of the gill-net fishing season, the 1st of October, has been offered to the Imperial House of Japan. Perhaps this explains why Wakasagi written as ワカサギ is also spelt as 公魚 (Meaning Official Fish in Japanese kanji.)

“When they were first moved from Kasumigaura, they were probably left to spawn naturally, but improvements were gradually made by people adding to their numbers.”

Wakasagi containers are brought in one by one from various points around the lake.

The challenge is how quickly they can be transported from the fishing grounds to the hatchery tanks.

They then began to purchase fertilised eggs from Hokkaido and other places to hatch, as well as conduct an egg harvesting business for Lake Ashi’s Wakasagi smelt.

“Like salmon, the female eggs were squeezed out and sprinkled with male sperm. However, it is very labour-intensive, and the eye-up rate is poor. Of course, both male and female Wakasagi die. The current egg harvesting method was developed through trial and error attempting to improve the eye-up rate.”

The spawning season for Wakasagi in Lake Ashi usually starts in March. Therefore, the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative catches Wakasagi every day from the 2nd of March until about the first week of May. Once the fish are released into the tank, they are first covered with a screen to block the light. This helps to calm the fish down and encourages spawning behaviour. After 20 hours or so, the spawn begins.

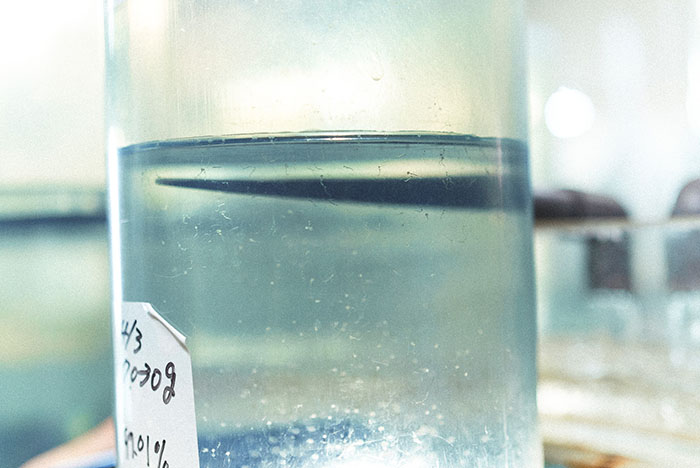

“The tank has two layers, divided into an upper and lower section by a board with numerous 4 mm holes. (The holes are large enough to allow fertilised eggs to pass through but not the adult fish.) This allows the fertilised eggs to accumulate below the board.”

In nature, the eggs are highly adhesive and do not float, as they are laid on small gravels on the lake bottom. Although some eggs may remain on the board, most collect in the lower layer, which is then carefully gathered with bare hands.

“Trout eggs are vulnerable to change, but Wakasagi eggs are not. The grown fish are often preyed upon by other fish, and perhaps because they support the foundations of the ecosystem, the eggs themselves are very strong. Their strong vitality allows them to increase in number and protect their species, which in turn supports the food chain in Lake Ashi.”

The eggs carefully gathered by hand are golden brown in colour and about the size of cod roe. The full-grown fish is only about 5 cm long, so the eggs seem large for its size.

“The eggs are then agitated with ceramic clay and treated to remove adhesiveness.”

Removing adhesiveness, also known as degumming, reduces unwanted substances and lowers mould growth. Incidentally, many eggs in their natural state laid on the lake bottom are mouldy.

“Then, they are transferred into this incubation cylinder. Inside the cylinder, the fertilised eggs hatch in the convection of pumped-up groundwater.”

Manually removing other fish species and debris from the nets.

The fertilised eggs collected on the same day are all placed in the same single incubation cylinder: for the first three days, the cylinder is filled with the golden colour of the eggs. Then, it gradually becomes darker.

“These are called eyed eggs where the eyes are formed within the egg. When this happens, body tissue forms within the egg.”

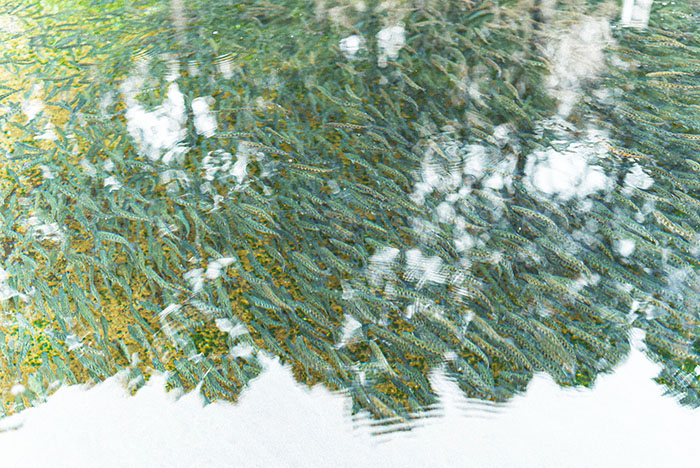

Hatching begins ten days to two weeks later. It is as if little fairies are floating around inside the cylinder. The fry is then sucked into the waterway from the top of the incubation cylinder and returned to the lake.

“The number of days for hatching depends on the water temperature. The groundwater here is always stable at 13.7°C, so it is easy to manage. The lake water at the beginning of March is about 6°C, which means it takes twice longer to hatch. However, it doesn’t mean warmer water is better. Excessive heat causes heat shock and leads to mould and disease development. As it happens, 13.7°C is the ideal water temperature.”

Eggs, after degumming, shine beautifully.

An incubation cylinder containing eggs. The far-right cylinder contains eyed eggs.

The adult fish in the tank is released to the lake after one night. Although some die, most return to the lake in good health. ”Wakasagi is an annual fish that lives for one year, but they spawn several times in that year. The maturity of the eggs each fish has differs from one to the other.

If immature eggs are forcibly squeezed out, the eye-up rate is low. Instead, if fish that have not spawned are returned to the lake alive, they can be caught again at the right spawning time. And it is also possible to collect eggs from Wakasagi that are showing spawning behaviour once again.”

As mentioned above, Wakasagi is also fundamental to the lake’s ecosystem as prey for trout, largemouth bass and other species living in Lake Ashi. Returning them to the lake without killing them for a single egg harvest makes sense. The most important thing is that with this method, the eye-up rate is over 90%, whereas, with the conventional method of squeezing, it is less than 50%.”

Eggs hatch between 10 days and two weeks after harvesting.

The hatched fry are returned to the lake.

This natural spawning method by the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative is known as the ‘Lake Ashi method’ (Lake Ashi natural spawning method).

“This method started to take off in the year 2000. Professor Moriyasu Kudo of Tokai University, the then union leader Mr Motoo Ohba along with the Cooperative members developed this method through a process of numerous trial and error.”

Professor Kudo, who was engaged in inland fisheries for a long time, hoped to contribute to the improvement of fishery technology. With respect to his wishes, the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative has made all its technology and method, from egg harvest to stocking, widely available to other Fishery Cooperatives.

“With the previous method, the first step was to separate the male and female fish. When you catch 100 kg, no amount of manpower was enough!!”

However, with the Lake Ashi method, even with a 100 kg catch, four people can finish the work in the morning. Another positive aspect is that by repeating the cycle of hatching eggs harvested from where the fish actually live, Wakasagi grows in a way that best suits the environment.

Fertilised eggs from Hokkaido grow around May due to its cold water temperature; if the eggs arrive in mid-May, they will be slightly out of sync with the environment of Lake Ashi.

“At the time, the lake’s Wakasagi spawned over a six-month period from late January to late June. As they are annual fish, the difference in spawn period was significant, resulting in fish with varied sizes across the year. When the Lake Ashi method was established, spawning was concentrated in March through April, and the size of fish began to be uniform. This is the cycle of Lake Ashi and is probably a natural cycle. For the past 22 years, we have never placed eggs from other lakes into ours.”

Egg harvesting continues every day from the beginning of March to the beginning of May.

Wakasagi is being brought to the hatchery one after another as we talk. The work is carried out quickly and carefully so as not to weaken the fish. We ask Mr Yosuke Yuki, who bends his large body and works silently with his hands, how many eggs he can get from a 50 kg haul. “The eggs you get from Wakasagi are about 10% of the catch, so 50 kg would be about 5 kg… 1 g contains 2000-2500 eggs, so 10-12.5 million,” he replies.

The eye-up rate marked on the incubation cylinders is calculated by Mr Yuki himself, who counts 1,000 eggs with the naked eye and determines whether the eggs are alive or dead. He used to count up to 50,000 eggs and then calculate the percentage, but he found that counting 1,000 gave a more credible figure.

If 10 million eggs hatch every day, that is 600 million fish in two months. Wouldn’t this conversely lead to an overabundance of Wakasagi? “Actually, a situation like that happened a few years ago. Perhaps the saturation of the lake exceeded, and the average size of the fish got smaller. At that time, we were hatching and releasing 500 million eggs, but now we keep it down to 300 million. Five years have passed since then, the average fish size has grown back to its original level, and the egg hatchery project has not been hindered. This number seems to suit the environment of Lake Ashi.”

Mr Yuki smiles, and Mr Fukui takes him at his word. “Because greed never does you any good.”

Work continues with bare hands in the cold groundwater to avoid damaging fish and eggs.

Wakasagi from Lake Ashi is also known for its excellent taste. When asked about the secret, Mr Fukui says it lies in the quality of the water. The lake in front of him is a deep blue colour, like the Kuroshio Current running through the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

“During the period of rapid economic growth, pollution rose. In the 1980s, when we were in primary school, the water clarity was about 50 cm at its worst.”

Before overseas travel became common, Hakone Town was a significant tourist destination. However, the accommodation facilities around the lake at that time did not have sewage treatment facilities. When pollution increases, the dissolved oxygen at the lake bottom is consumed. This affects and damages the trout species that live in the deeper part of the lake to avoid high water temperatures.

Even if the shallow area can take up oxygen from the waves or wind, the surface with the high temperatures is not suitable for the trout to survive.

“That situation continued until in the 1990s when the public and private sectors started to work together to improve the public sewage system. It took about ten years, but the water quality finally returned to normal at the beginning of the 2000s.”

This coincided with the time at which the Lake Ashi method was established. Another innovative decision was made at this time by the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative to ban the use of plastic worms.

“Worms left at the bottom of the lake, for example, by snagging, are swallowed by cherry salmon and largemouth bass. The worms remain in their intestinal tracts leading to fish becoming emaciated and dying without being able to eat any live food. In order to raise healthy fish, we had to put a ban on their use.”

Beautiful Wakasagi are brought in one after another. Even though it is a familiar scene for the cooperative members, there is an uplifting atmosphere in the hatchery.

The outcry against the ban on using worms, which can produce explosive fishing results, was significant. Although Fishery Cooperatives were created to increase fishery resources, by then, many cooperatives were keen on developing enjoyable recreational fishing (angling).

Despite various opinions, the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative chose not to pursue short-term profits but to ensure that the lake nurtures beautiful and healthy fish in a sustainable way. This determination led fishing manufacturers to produce biodegradable worms and, as a result, has influenced other lakes to follow their steps.

“Along with that, there is an abundance of zooplankton for the Wakasagi to feed on. That’s why the Wakasagi in Lake Ashi grow so quickly and is the reason why we are able to start the Wakasagi fishing season in July, the earliest in Japan.”

Is this due to the topographical reason that it is a caldera lake with no incoming river?

“We conduct monthly surveys with the help of Kitasato University and the Fisheries Experiment Station in Kanagawa. Why is Lake Ashi so efficient in producing zooplankton? ……”

Although this is only a theory, Mr Fukui continues to explain. He describes that normally, there are rivers between the lake and mountains. However, Lake Ashi is in close proximity to the mountains and does not have any roads that block a stable supply of nutrients from the mountains. This may be one reason for phytoplankton to occur, and zooplankton may benefit from this. “Still, I don’t think it’s so unusual that plankton grows and Wakasagi increase in numbers; I think it’s nature’s way of doing things. There are lakes in Hokkaido where the number of Wakasagi has remained stable for a long time without any egg harvesting projects. If we are able to restore the lakes to their natural state, their productivity will naturally increase.”

A memorial monument for the fish is set up near the fishponds.

As they tell us these stories, the members of the Fishery Cooperative continue to move around and work. Mr Isoroku Takanashi, who continues to remove debris from the fertilised eggs, laughs off the idea of sticking his hands in the cold water at all times, even though he tells us he is fine with it now. “The design of the tanks, the idea, the two-layered system were all our ideas. That’s how we are leading the way in the Wakasagi egg harvesting project…and that’s where the joy is.”

They modestly tell us that the Lake Ashi method had won the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Award. Mr Fukui and Mr Yuki say that their memories from when they attended the local primary school are what keep them going today.

“At the time, we had egg harvesting and fry release in primary school classes.” Hakone Town’s people know that Lake Ashi is famous for its Wakasagi, but less is known about the egg harvesting project that supports it and the rich nature that Lake Ashi maintains.

The pair wish to pass down the attractiveness of this land and communicate the importance of protecting the lake’s creatures and environment to the next generation. As with many other Fishery Cooperatives, the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative is struggling with a lack of successors, but their pride, joy and genuine feelings are present in their bashful smiles.

“With this in mind, we provide Wakasagi to elementary schools in the town for use as ingredients in their school lunches. Some classes incorporate the Wakasagi egg harvesting project into their lessons.”

Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative consists of about 150 members, ages 24 to 61.

A Yamame trout swimming in an aquaculture pond. They are very clever and vigilant. They remember the face of Mr Yuki, who feeds them every day and runs away as soon as anyone else approaches.

They have also revived the fry release project that they themselves experienced as a child. The eggs are harvested with the children from the fish swimming upstream in autumn and then incubated fry are released in spring when Grade 1 students enter school. Then, in autumn, the fish is once again caught… so continues this cycle and the tradition.

It is their belief that this will remain in the hearts of the children, and they will grow up with a deep understanding and appreciation of their hometown.

So what is this fish, which, like the Wakasagi, is deeply connected to the history of Lake Ashi and is also known for its delicious taste?

When I asked him about it, Mr Fukui smiled and replied, “If you want, you can come and visit us at our anniversary release in May!”

Helly Hansen, the outdoor brand created by Norwegian sailors, supports the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative.

Hakone Town is blessed with its beautiful and unique landscapes created by volcanic activities, while it has also been a major gateway to transport since the Edo period, resulting in a rich and quaint culture of its own. Hakone Town has a “Comprehensive Agreement on Regional Revitalisation” tie-up with Goldwin Inc., a company that promotes regional development from the perspective of various cultural and outdoor activities.

The yellow hood and high collar are helpful in the cold mountain lakes.

As part of this, the Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative is supported by the Norwegian-born marine brand Helly Hansen, which is carried by Goldwin. We ask how the cooperative members find the high-functional wear loved by fishermen and workers at oil fields in the northern lands.

“It’s light and warm, of course, but it’s also long-lasting and durable, with waterproof breathability and other features,” Mr Fukui comments. His favourite Brisklite jacket is a light model, but he says it provides enough warmth in freezing February conditions with spray and requires only a layer of fleece inside.

“On top of that, it helps that the cuffs, ankles and other openings fit and close tightly, disabling any water, let alone cold air, to get in.”

Careful attention is paid to details, and one example is found in the yellow hood.

‘At first, I wondered why they were so bright in colour, but it’s to make rescue easier if a member were to fall overboard. So I am very conscious about keeping my hood out when I am on the boat, even if I don’t have to wear it.”

In addition to these functionalities, Mr Yuki follows on to remark how he feels. ‘When we all wear the same clothes, it simply raises the spirits. The Fishery Cooperative is also a group of professionals, so we need to dress accordingly. It’s great when the kids think we look cool! I would be very happy if they do.”

"When I put my arms through this jacket, I feel a sense of responsibility and significance," says Mr Yuki.

The sleeves, ankles and neckline are double-layered to prevent water and cold from entering.

Photo by Masaya Kudaka

Text by Koki Aso

Translation = Asaka Barsley

Direction by Shin Kaneko

Interview supported by Lake Ashi Fishery Cooperative Association.